Seeing

My sister and I currently visiting pals in New Hampshire for a few days. You know: that couple with the great house on a lake, with Blue Herons nesting, and Canada geese raising their babies.  And Ming, the famous Birman cat. It’s lovely and restful here… I’ve basically just been chilling and reading and chatting.  Very little blogging or writing this week!

But one doesn’t stop thinking.  And one thing I’ve been considering about the upcoming book is the matter of how new steerswomen are made. That is: the Steerswomen’s Academy.

And in light of that, I find myself circling ideas about how we see, and how we interpret what we see; and how a steerswoman has to approach what she observes without the usual built-in biases.

And drawing: a steerswoman will be sketching and drawing a lot in her travels. She needn’t be artistic, but she must be accurate.

Of course, artistry is permissible if it doesn’t compromise accuracy! And there’s nothing to prevent a steerswoman with an artistic bent choosing to also do artistic, evocative and imaginative images unrelated to her work as a steerswoman (as long as she doesn’t pass them off as being entirely factual!).

Of course I’ll be revisting Betty Edwards’ Drawing On the Right Side of the Brain. Of course.

But sometime in the last couple of weeks, I was directed — I can’t now recall by whom — to this set of images:

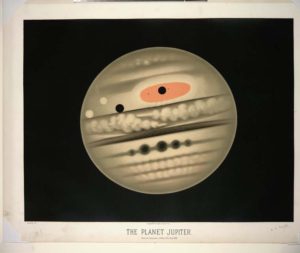

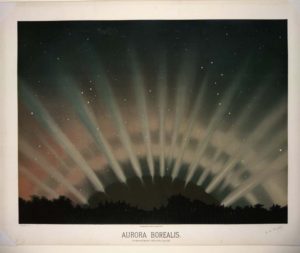

These are drawings by Étienne Léopold Trouvelot, a french artist and astronomer working in the 19th century, at a time when astrophotography had not yet hit its stride, and science depended more on images drawn from observation.

They’re from the New York Public Library’s Digital collection.  (Click on any image to go to their website and see the rest.)

I find them lovely and inspiring.

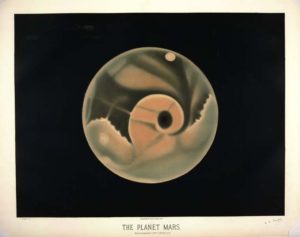

But I do wonder here, how much was seen, and how much assumed?

For, example:

Notice the canals? They’re right there.

Except… there never were any canals on Mars.

Starting with the observations by Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877, people saw canals on Mars. And drew them. Even mapped and named them.

And they were never there.

Once photography improved, and its use in astronomy became common… people began to notice that no photograph ever showed a canal on Mars.

We are human beings, and we are pattern-seeking creatures.  We’ll piece together fragments and glimpses into arrays that make sense to our eyes and our brains… and we can be fooled.

But when you discover that you’ve been wrong — that is itself a discovery.  And then the knowledge that replaces the error slots into position: a very satisfying feeling.

New knowledge: what could be cooler?

It’s all about discovery.