Seeing

My sister and I currently visiting pals in New Hampshire for a few days. You know: that couple with the great house on a lake, with Blue Herons nesting, and Canada geese raising their babies.  And Ming, the famous Birman cat. It’s lovely and restful here… I’ve basically just been chilling and reading and chatting.  Very little blogging or writing this week!

But one doesn’t stop thinking.  And one thing I’ve been considering about the upcoming book is the matter of how new steerswomen are made. That is: the Steerswomen’s Academy.

And in light of that, I find myself circling ideas about how we see, and how we interpret what we see; and how a steerswoman has to approach what she observes without the usual built-in biases.

And drawing: a steerswoman will be sketching and drawing a lot in her travels. She needn’t be artistic, but she must be accurate.

Of course, artistry is permissible if it doesn’t compromise accuracy! And there’s nothing to prevent a steerswoman with an artistic bent choosing to also do artistic, evocative and imaginative images unrelated to her work as a steerswoman (as long as she doesn’t pass them off as being entirely factual!).

Of course I’ll be revisting Betty Edwards’ Drawing On the Right Side of the Brain. Of course.

But sometime in the last couple of weeks, I was directed — I can’t now recall by whom — to this set of images:

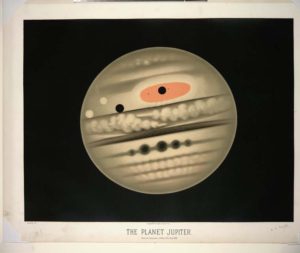

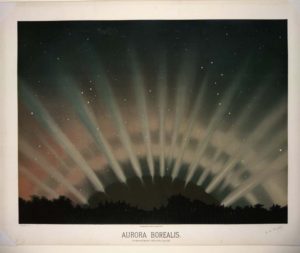

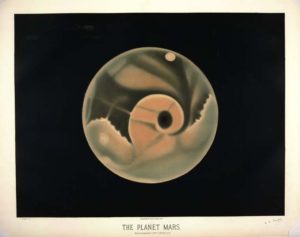

These are drawings by Étienne Léopold Trouvelot, a french artist and astronomer working in the 19th century, at a time when astrophotography had not yet hit its stride, and science depended more on images drawn from observation.

They’re from the New York Public Library’s Digital collection.  (Click on any image to go to their website and see the rest.)

I find them lovely and inspiring.

But I do wonder here, how much was seen, and how much assumed?

For, example:

Notice the canals? They’re right there.

Except… there never were any canals on Mars.

Starting with the observations by Giovanni Schiaparelli in 1877, people saw canals on Mars. And drew them. Even mapped and named them.

And they were never there.

Once photography improved, and its use in astronomy became common… people began to notice that no photograph ever showed a canal on Mars.

We are human beings, and we are pattern-seeking creatures.  We’ll piece together fragments and glimpses into arrays that make sense to our eyes and our brains… and we can be fooled.

But when you discover that you’ve been wrong — that is itself a discovery.  And then the knowledge that replaces the error slots into position: a very satisfying feeling.

New knowledge: what could be cooler?

It’s all about discovery.

April 28th, 2016 at 6:54 am

I got curious enough to try to match Etienne’s drawing with actual mars topography, courtesy of Google Earth. The bright spot on top is probably the the north pole, but I couldn’t find a good match for that large dark spot surrounded by a large brighter area in the middle. I did notice, though, that Valles Marineris is visible as a long straight line. So it might have been that.

April 28th, 2016 at 11:41 pm

Michael: one thing to remember is that nowadays we display images and maps of Mars with north at the top; but traditionally in the past, south was at the top. This was because celestial telescopes inverted the image, due to the way light moves through lenses. They could have had a right-side-up image by adding another lens to the configuration (as is done with telescopes meant to be used to observe things on earth), but each extra lens, while magnifying the image, also eats a bit of the light. In viewing celestial objects, you want to keep as much light as possible!

So, that white bit on the top is the South Pole. If you take a modern map of Mars and turn it upside-down it’s easy to identify that downward-pointing triangular dark area as the famous Syrtis Major. And it looks like that dark spot surrounded by lighter areas would be Sinus Meridiani.

April 29th, 2016 at 2:36 am

There’s also the problem of color distortion around the edges of the lenses. The more lenses stacked up, the greater the distortion. That’s the big advantage of a Newtonian telescope, the main light collector is a parabolic mirror which eliminates that distortion. You still need a lens for the eyepiece (or camera nowadays).

April 28th, 2016 at 7:55 am

I really like the Jupiter – it is a heady combination of artistic license and what it looks like, but yeah, Mars’ canals…

April 28th, 2016 at 9:21 am

Pattern-making. Gets us in lots of trouble, I think. As to accurate reporting, I remember a line from one of Heinlein’s later books where there is a class of worker called Witness. The woman is asked “what color is that house over there,” and answers “it’s white on this side.” If only, I thought then (and now), if only everybody could learn how to make accurate statements. I suppose we wouldn’t be human then, would we?

April 28th, 2016 at 7:39 pm

Could’ve avoided those really oddly maneuvering meteors though, if someone had recognized a pattern there 😉

(I’m not sure I like the drunken one, the one who decided to turn around in disgust or the one who pinged of an invisible alien space ship orbiting Earth more interesting)

April 28th, 2016 at 11:12 pm

Ben: I think that since all the meteors were all in motion, it was especially hard to capture their exact paths. Also, there’s the movement of one’s eye when glancing about at all the stuff going on. It could be easy to mistake the zoom of a light across the retina as due to the motion of the meteor instead of the motion of your eyeball.

That’s assuming that he did see that many meteors all at once, and not that he was adding up what he saw across several hours or nights.

I don’t think that the famous autokinetic effect came into play; that tends to operate when looking at a light without other reference points.

April 28th, 2016 at 7:37 pm

Lindig, I also thought of the Fair Witnesses from _Stranger in a Strange Land_ when I read this post. Alas, Heinlein was befuddled by Korzybski and “General Semantics” around then, and overestimated what even trained observers can reliably observe. I think baseball umpires are my favorite current example. At the major league level, they are incredibly highly-trained at pattern-matching of a very specific sort — and yet we now have technology that reveals that they get it wrong a stunning fraction of the time, even in extremely clear-cut cases.

April 29th, 2016 at 2:51 am

I’d be interested in stories about the Steerswomen’s Academy. Seeing Steffie’s reactions to things might be especially interesting.

BTW, should “Berman” be “Birman“?