Jack Hardy and three tons of bricks

It was 1982 or thereabouts, in New York City, and I was walking up MacDougal Street with Jack Hardy.

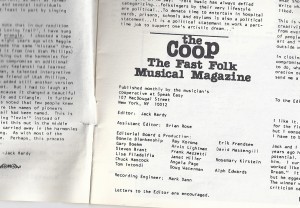

It was early evening, and a meeting had just ended at his apartment on Houston Street. I’m pretty sure it had been a staff meeting for the Fast Folk Musical Magazine; there was a songwriter’s exchange that also took place at Jack’s apartment, but I can only recall having been at a couple of those. More likely, a Fast Folk Musical Magazine meeting. I was always at those.

The meeting had broken up, and we were on our way to a different meeting, this one for the Musician’s Coop as a whole, taking place at the Speakeasy cafe. It seems to me, in my memory, that there was always some sort of meeting of some sort going on during that period, and this was not a bad thing.

I remember walking up that block of MacDougal sitting between Houston and Bleeker, and how that was a route that I rarely took, making the surroundings seem vaguely exotic to me. The empty basketball court, the trash cans, the quiet, brick buildings with no one out on the stoops – more residential than the block above Bleeker, where the Speakasy was located.

I was having one of those “Hey, I’m in New York†moments I often had in those days. Hey, I’m in New York. Walking toward Bleeker Street. With Jack Hardy.

The meeting at Jack’s had been pretty big, and we were not the only ones heading up to the Speakeasy from there, but for some reason we had all spaced ourselves out, some running ahead, some lagging. I was lagging; so was Jack. Which put me more or less alone with Jack Hardy, walking up MacDougal.

Conversation was called for. I was still agonizingly shy in those days — but Jack wasn’t saying anything, so it seemed to be up to me.

“You know,†I began, “I was listening to “ — I’m sorry, I can’t recall the particular song after all this time, but it was one recently recorded on the Fast Folk Musical Magazine — “and I noticed the harmony… That was you singing, wasn’t it? I mean, that really gorgeous, really high harmony part?â€

He laughed. Jack had an interesting laugh: a one syllable, one note, huh! It could mean surprise, amusement, derision, self-deprecation, sarcasm, any or all in combination. (Listen for it on his live recordings. It’s there.)

He made that sound now. Then: “Yeah, that was me.â€

“It was… so high, and pure…â€

And different. Jack was famous for his odd, creaky, voice: sometimes more breath than note, or a grinding grumble, or a ringing tone like a cracked bell.

I once remarked to a friend that I really liked Jack’s singing voice. Friend: “You like it? But, but he sings like — like the Devil himself!†Me: “Aha! That’s it!â€

Jack seemed to sing from some place different from the other singers I heard. Some ancient, dangerous place. How could I not like it?

But that was not what I had heard on that recording. Jack’s part was the top line of a three-part harmony, and it had been high, clean, pure and flawless.

I had to check the credits on the album track. I knew the other voices, and recognized them. By process of elimination, the top part had to be Jack. The guy with the voice like the Devil himself could also sing like an angel.

“That’s my natural voice,†Jack said. “I’m really practically a counter-tenor.â€

“Wow. So… why don’t you sing like that more often?â€

“You can’t deliver text up there.â€

I don’t think that I actually stopped short in the middle of the sidewalk and stood dumbfounded; but I do know that I did the exactly corresponding mental equivalent of that.

Like the saying. Like the cliche. Ton of bricks.

Because, here’s the thing:

I sang high. It was fun. I could hit all these crazy notes, how cool is that?

But every now and again, someone would say something like: Maybe you shouldn’t be singing that high. The suggestion was usually imparted almost reluctantly, tentatively. Um, you know… maybe you should try singing… lower?

But other people — many, many more people, in fact — told me that they liked my voice. So, I had a quandry: who do I believe?

Well, Believe yourself, the self-improvment gurus today would say, decide what YOU like! But I was just learning my craft back then. You don’t learn by sticking to your guns no matter what. You learn by paying attention, and discovering more. You learn by thinking about what you hear, and finding out what it means.

Ninety percent of the people who expressed an opinion to me said that they liked my voice. However, the handful of people suggesting I sing lower were people whose opinion I valued.

But whenever I asked them the obvious next question, Why?, they had no useful answer. It would sound better is just too vague. It’s too obviously based on personal taste. I don’t know, high just doesn’t…work…

But why not? In what way doesn’t it work? What’s an example of it not working?

I continued to get no real answer. And given that I could not decide between two contradictory sets of information, I opted for No Change.

Because, if you’re talking about art, and some people like it, and other people don’t, then it’s probably just a question of taste. Right?

But: You can’t deliver text up there.

And text is the thing, text is the critical element. Text was what made this music the music I loved.

The music I heard as a kid was all Baby, Baby, I need your love, Love me, do, My baby done me wrong, can’t live without that man of mine, my boyfriend’s back and you’re gonna be in trouble. It wasn’t until my sister brought home a record of the Newport Folk Festival that I found out that there were other things to sing about.

Mining disasters. Indian rights. The cycle of time. Life, death. Longing, anger. Trains. The war in Vietnam. Emilia Erhardt. Take a stick of bamboo and throw it in the water, dammit. My home’s across the river.

Love, sure, also love; but not only love.

The whole world; this was the music that let you sing about the whole world. Folk music, or urban folk, or contemporary folk, or literary folk — the terms aren’t clear, and the categories blend into each other, but the word folk keeps recurring.

Folk music — that was the stuff, and the text mattered.

When you sing very very high, the note distorts the word. The physics of achieving the note alters the shape of your mouth. Your language sounds unnatural when you’re hitting that high C. You’re subverting meaning in favor of vocal gymnastics.

Sure, you can deliver text up there — if your text is la, la,la, or oooo-ee. I have a little more to say than that.

So, with Jack Hardy’s casually dropped ton of bricks, I suddenly understood what my friends had been unable to get across to me. It made artistic sense. And I started singing lower.

Some people prefer the way I used to sound; some people prefer the way I sound now. What matters is that I see the connection between how I sound and what I say. Text matters.

That was ton of bricks Number One.

Here’s ton of bricks Number Two:

Back before the Fast Folk, and before the Musician’s Coop and the Speakeasy Cafe, I had a part-time programming job in Jersey City, right across the river from New York. I’d stay in Jersey City during the week and head home to Connecticut for the weekends.

This, I thought, was my opportunity to check out the music scene in New York, without having to actually live there (that came later). So I wandered over one evening, and checked out the Open Mike at Folk City on West 4th Street.

(I could go on and on about Folk City, and I will one day; but not now.)

And I do believe that it was that first night, as I was making my way across the room, when I heard the people on the stage sing:

Ruin has him in the wind at last,

Cries the Wolf of Time.

And I remember thinking: Wait, you can do that in a song? And it’ll work?

This was Jack Hardy, with his brother Jeff on upright bass and his brother Chris on fiddle, both brothers doing backup vocals. And this was my introduction to the literary song.

Some other practitioners were Brian Rose and Suzanne Vega — and there were plenty more where they came from, as the saying goes. But Jack’s voice was the first I heard doing something identifiably other than what I expected of Folk Music up to that time. The literary song is not just the subject matter, it’s how you use the language. And Jack not only did it, he talked about it, promoted it, communicated with other musicians on behalf of the idea.

You can sing about anything, and you can use poetry to do it.

One more revelation from Jack Hardy (ton of bricks Number Three), and I’m calling it a night. It’s late; I’ve been at this a while.

As I found out when I started going to Greenwich Village, and hitting the Open Mike nights, there really was a music scene for folk music in its various incarnations.

But it was cut-throat, difficult, limited. Small, and hard to break into.

Somewhere in there, an idea started circulating, and I don’t know who came up with it, but it was this: We can make a music scene. We can create one. But first, we have to work together. And the Musician’s Coop was born.

And then somebody (if you know who, please tell me) approached the owner of a languishing cafe with the offer of: you provide the place, we provide the music; we get the admission price, you get the money from all the drinks and dinners. And the Coop had a home base.

I jumped aboard pretty quickly; I was not one of the original instigators, but I gave it my all. My best contribution was running the sound board.

But out of the Coop, came the Fast Folk Musical Magazine. It was, if memory serves, Jack Hardy, Brian Rose and Angela Page who were the instigators. It was such a radical idea: a magazine that included a vinyl LP. Issued monthly. Non-profit.

This was before the Internet. No easy communication, no singing into a mike attached to a computer to get an near-instant MP3 file. No YouTube. Records were expensive and hard to make.

It was a brilliant idea that was also stunning. We could do it. Ourselves.

I wasn’t on staff for the first issue, but by the second issue, I was right there.

And that’s the third revelation, third ton of bricks: You can do it.

If there is no place for you, make a place. If no one’s doing what you need done, do it yourself. If no one can hear you, create a forum.

If you don’t like it, change it.

I could go on.

I could tell you about the Tinker’s Coin, which I’ve actually seen; or about how Jack rose to my defense on radio in Italy; or the night we argued about which was more important, truth or beauty? (You can guess which side I came down on.)

But here’s the thing: I like people who rewire my brain. I like to be startled, to be turned around, and to suddenly see everything from the opposite side.

I honestly don’t know what Jack’s opinion of me was, other than that he liked what I wrote for the Fast Folk. I have no idea what he thought of my music. (Perhaps he thought I was singing too high?) It’s irrelevant, really.

Jack was an important figure during an important period of my life, and he rewired my brain over and over.

He had ideas, and he put them to work. He had views, and he stood up for them.

He made things happen.

It mattered that he was here; it matters that he’s gone.

Jack’s obituary in the New York Times

[addendum: Musician Josh Joffen tells me that it was Angela Page and Vincent Vok who approached Joseph Zbeda, the owner of the Speakeasy, about the deal with the Musician’s Coop. Vinnie Vok was literally the first person I ever met in Greenwich Village, when I walked up to him in the sign-up line at Folk City, and asked, “Hey, what’s going on here?”]