Readercon: my reading.

I had started writing a post analyzing that Sturgeon quote, and was rather enjoying myself, but suddenly found myself in a time crunch with three different tasks that need my immediate attention.  I had to set it aside; I’ll get back to it next week.

So, instead, I’ll tell you about my reading at Readercon

Yes, they were able to assign me time for a reading! However, Book Five is currently still in a state of chaos, and the only non-chaotic parts parts are either major spoilers, or stuff I’ve already read at readings, far too many times. So instead, I read a couple of chapters from a side-project of mine (not the fabled Seekret Project).

I’ve long had an idea that it might be fun to write a YA (Young Adult) book that would take place in the Steerswomen’s universe. So, every now and then I cool my fevered brain by doing some work on that.

To my mind, the main differences between YA and Adult fiction are: 1. Age of the protagonist; 2. size of the vocabulary; 3. degree to which the sentences are convoluted, clause-filled, and of esoteric construction. I’ve attempted to keep to those parameters, but not very assiduously; I’ll fix it all in the rewrites.  Mainly, I just wanted to start getting things down on paper.

And that’s what I read from at my reading.

The working title is:Â TRUTH, ALWAYS.

CHAPTER ONE

It made no sense, no sense at all.  Amy stood staring at the boy; she couldn’t even guess what expression was on her face.

He really was going to hit her. “You don’t even know me,” She managed to say.

“So?” He stepped forward again, his fist still cocked; she stepped back again. “Stand still,” he said in a tone of complaint, as if this were something they had both agreed to, as if she were trying to cheat him.He stepped forward again. She stepped back.

She wasn’t even frightened, although she thought she perhaps ought to be.  And then she realized that she really was frightened — but not by the fist, nor the twisted expression of hate on the boy’s face. It was that it simply made no sense.  That was frightening, in a way that was hard to understand… somehow weirder than the autumn ghost-tales, and scarier than feeling the lake ice move, just a bit, silently, beneath your feet when it was midnight, and the stars were high, and you were still a mile away from shore.

Because, although you could die from drowing under the ice, at least the ice made sense.  Even ghosts had their own sort of logic. Without that logic, ghosts couldn’t happen at all, she guessed.

But this strange boy, to whom she had spoken perhaps only five sentences, wanted to do her harm, for no reason.

That was the frightening thing; that there was a time and a place where a thing would happen for no reason.  And the thought of that made everything else crumble.

No, she told herself. No, things made sense, they had to make sense. People did things for reasons.

Meanwhile, the boy had kept stepping forward, and she had kept backing away; and now her back was right against the rail, and the blue, cold Aizi was beyond that. She could back no further.

She felt for a moment that she could do absolutely nothing — because, how could arms and legs and breath ever work at all, if the world made no sense?

Then she remembered what her eldest sister Lilly had said: that bullies were really cowards and would back down if you stood up to them.   So she took a step forward.

It didn’t work. He didn’t back down. That fist that he was holding up moved, no hesitation at all.

His aim wasn’t good.  He hit her arm, but not square on – just at the edge, and his fist slid past and thumped up against the railing. He yelped and snatched his hand back. “Look what you did!” There was blood on his knuckles.

“What I did?” She stepped to one side, wondering why her arm didn’t hurt; and then it did, but it wasn’t much. Hardly as bad as a skinned knee. For a boy so eager to fight, he seemed not very good at it.

Then he made a wild noise and came at her, flailing.

But before he reached her, he fell backward, suddenly, jerked back and sent sprawling and sliding across the deck.  His face was all astonishment.  A moment later, the tip of a cane was planted on the center of his chest, and at the other end of the cane was a hand, and the hand belonged to Simon.

He stood gazing down at the boy, not with anger, but with something like curiosity.  The boy tried to get up, but Simon seemed very strong for an old man, and there was no result at all.  “Ow,” the boy said — not a real cry of pain, but just the word, spoken.

Simon tilted his head. “What’s your name, boy?”

“Ow. Let me go!”

“Hm.” Simon thought for a moment, then lifted his cane just a bit. The boy scrambled back like a crawfish, then got to his hands and knees and escaped, pounding around a cabin housing and away somewhere.  Two of the crew, a young man and a woman so old she looked like she was made of dried fish, parted as the boy dashed between them. They exchanged a glance, then looked at Simon.  They went back to their work.

Simon turned to her, and displayed his grin, which contained only six teeth, each solitary but in perfect condition. “I don’t think you’re hurt, are you, Amy?”

“No… I’m all right…”

“What did you say to him? That he got so angry?”

“I don’t know!” She couldn’t see the boy any longer; he had vanished, lost among the other people wandering the deck, or perhaps run below into one of the cabins. “He asked me where I was going, and why. And I told him, and he called me a liar. And then he came at me!”

“Hm. Well, if you see him again, and I’m nearby, just grab my stick and give him a good solid whack. Don’t wait for him to come at you; take the initiative! I’ve found in life that action is better than dithering, and a wrong decision is usually better than none.â€

Amy instantly thought of half a dozen situations where that would not be true at all. But to be polite, she said: “Thank you. I’ll keep that in mind.â€

And he and his cane would be nearby, she knew, at least at night. He was going to be sleeping in the common-cabin with her.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Cassia should have been here. That was the plan: Amy and Cassia traveling together. They had agreed, it was settled, and they should both be here.

If Cassia were here, she’d know what to do about the boy; or if she didn’t know, she’d go ahead and do something anyway, something graceful and smart. That boy wouldn’t bother them if they were two together. And people never gave Cassia trouble, anyway — she could always talk them out of it. By the end of the conversation, they’d be on her side, and they’d even stand up to anyone else who tried to bother Cassia and Amy. That was how it worked.   Everything worked out best when Cassia was around.

But she wasn’t here. She had missed the boat.

Amy had asked the captain, said she knew that Cassia was on her way, was almost there, was going to show up at any moment. And the captain did wait, for a while.

But Cassia never arrived.

So the ship set sail, leaving the mountains and Beanberry behind, moving out onto the great blue Aizi. Beanberry disappeared behind the ship, replaced by more and more blue, the water now rougher than Amy had ever seen except during a storm, all odd random chop, small waves jumping crazily. The mountains behind the town seemed no further away at first, only growing bluer and dimmer. Then suddenly, between one moment and the next, they were far, and looked unreal, like a painted backdrop in a traveling theater.

It would take three days to cross the lake and reach Terminus, where there was a caravan the captain meant to meet. And another day after that to sail from Terminus to the headwaters of the Wulf.

Then Amy would have to walk. The river wasn’t navigable immediately south of the Aizi, so the maps said. Later, at Tintown, where the Kerrio River joined the Wulf, there would be boats, and then barges, and she could ride.

She had hundreds of miles to go.

And alone. She was surrounded by strangers.

#

Simon gave something like a bow. Amy couldn’t tell if he really knew how to make a courtly bow, or if he was making it up to tease her.  “Your choice, mistress,†he said, and waved at the hammocks.

Amy looked. They were hung one above the other, with just one wooden rung on the hull strut for a foothold to climb up to the higher one. Two by two in three sets, all down one side of the hold, right against the inside of the hull. The hammocks were on the right side, and on the left was the cargo: crates and boxes and barrels all lashed together in the center of the ship. And on the other side of that, Amy knew, another set of hammocks against the other side of the hull.

Simon was much taller than she was, and he seemed more at home in a boat than she felt. He was probably expert at clambering up. But the idea of some strange man just hanging above her, all night long – Amy hated the idea. “I guess I’ll go up.â€Â She had no idea how to do it.

“I thank you. And my bones thank you. And so does my bladder, which is exactly as old as my bones are but has more to say in the depths of the night. I’d hate to plant my foot on top of you when I climbed down at some personally urgent moment.”

This was more than she wanted to know, but she managed to say: “You’re welcome.â€

She waited to see if anyone else was going to climb into their own hammocks, so she could watch how it was done. There were cabins, on the next deck above, each with bunk beds and a door that closed – but they were far too expensive. Hammocks were all Amy could afford.

But it would have been all right, because Cassia would have had the other hammock. They would have laughed about it. Everything strange would have been just another part of the adventure, the two of them together.

Instead, here was Simon, and she ought to have been grateful, really. She actually was, when she remembered to be.

When Cassia didn’t arrive, the captain wouldn’t refund the money for her passage. It was too late — the ship had left the docks. Amy had paid for two people, but it wasn’t his fault that Cassia missed the boat.

In the lower hammock, Simon was already wrapped up in blankets and breathing deep. It was he who had saved the day. He had been planning to sleep on deck, wrapped in a blanket; the charge for deck passage was very small. But when he heard that Amy had an extra hammock, he offered to pay her. Not full fare, only half of what it really cost. But it was better than nothing.

Amy watched the other people climbing into the upper hammocks, and decided that it wasn’t as hard as it looked. It was all about balance and the way hanging things behaved — it was obvious where you had to put your weight, when she thought about it.

Then she put her left foot (not her right) in the foothold, grabbed the upright with her right hand, pulled herself up, switched hands, tilted back, and ended up on her back, in the hammok, looking at the bulkhead above her. She smiled to herself, with that warm feeling she always got when she solved something.

It was old wood, just inches away, and she wondered: How old? How many years had this ship been plying its way across the great lake, back and forth? It was beautiful and brave, really, when you think about it.

She could ask someone, she could ask the captain. Maybe there was a wonderful story about how the was ship passed down, generation after generation, in the captain’s family; or maybe he won it in a game of dice, and never thought to be a captain until he suddenly owned a ship! That made her laugh, to imagine that story: how he might have been very bad at running a ship at first, but then became good at it across the years.

It was lovely, all of a sudden, to be hanging in this tiny space, wood all above her and to her right, and the open passageway to her left. And even old Simon underneath her — who was he, really?  Wasn’t he sort of a puzzle, in his own way?  He was very nice to her, as odd as he was, with his very few teeth.

She forgot all about Cassia; until she realized that she had forgot all about Cassia, which was the same as remembering Cassia.

For a moment, she imagined that it was Cassia below her, breathing in sleep.

And that changed everything; everyone around would already be their friends, because that’s just how Cassia was.

And if that had been true, Amy right now would be glad and excited about the adventure they were undertaking. And she did feel that way: glad and excited, exactly as if her imaginings were real.

And then she thought, what an odd thing that was. How you can feel an emotion for something that isn’t even real.  It came to her that without Cassia, she’d be sad and lonely; it was the imaginary version of herself thinking that, while the non-imaginary her knew in fact that was what was really happening…

So, she set aside all those imaginings. No Cassia, and none of the things that Cassia brought with her.

But Amy found that she wasn’t sad. She wasn’t even lonely.

She was just… here.

There was enough light from a lamp down the passageway for her to see the beautiful wood above her. She reached up, and touched it; it felt old and rich. Then she put out her hand to the right, and laid her fingers and palm against the hull.

It felt like something alive was on the other side: the water itself, moving.  Or the ship moving, which amounted to the same thing, really. The whole of the lake, beside which she had lived all her life, for fourteen years, somehow alive.

And all one thing. She had not thought of that before. You could see the lake on a map, and she often had looked at it. But the part of the lake that she knew was just the part by Beanberry. Half the sky, in a way. Half the sky was sky above the lake, to the south-east. The other half of the sky was the mountains. They didn’t come all the way to the lakeside, but they stood to the northwest, owning the air like kings.

There were people living in the mountains, but you never saw them, so they might as well be imaginary; and there were people on the other side of the lake, but you couldn’t see the far shore. Everything in the whole world was either back of the mountains, or on the far side of Aizi.

But here: here it was. The moving water. Under her hand. Just on the other side of the wood.

She pushed her hand against it a bit harder; but all that did was make her hammock sway away from the hull. She let it sway back again, and used her touch on the hull to stop the swinging.

She was as stable as she was going to be.

She felt like things were slipping away from her on the one hand, but moving toward her on the other. She wasn’t at all sure what she meant by that, but that’s how it felt.

Could she fall asleep in this strange place? Whenever she had trouble falling asleep, she could always manage it by letting her thoughts run free, and imagining some sort of adventure.

One of her favorite things to imagine as she fell asleep, was that she was a steerswoman.

But that was exactly what was happening: she was going south, to become a steerswoman.

But was it a real adventure if there was no one to share it with? Is it really an adventure if you’re all alone?

Eventually, she managed to fall asleep by imagining clouds moving through the sky, forming and breaking up again, becoming more and more hazy, until they faded into sleep.

CHAPTER TWO

The door to the street opened, and a steerswoman entered.

This had been happening all day; had, in fact, been going on for a couple of months. No one thought it surprising any more. There were at this moment eleven other steerswomen in the tea-shop at tables in pairs. The newcomer made twelve.

This particular steerswoman stood a moment on the threshold, then laughed out loud.  Heads turned, and then hands lifted in greeting. One of the seated women rose and tried to wave her over, but the newcomer caught sight of something that interested her. She declined the invitation with a tilt of her head. She made her way across the room, swinging along on a pair of crutches, toward a table where one woman sat alone, knitting.

When the newcomer had crossed half the distance, the knitter paused, closed her eyes, and cocked her head. She smiled.  And when the newcomer arrived, the woman at the table put down her work in her lap, and said: “Zenna.”

“Impossible for me to sneak up on you. Even with Steerswomen’s boots. Well — boot.”  Zenna pulled out a chair opposite the other woman, then changed her mind and sat down directly beside her. They embraced.

“How are you?”

“I’m well,” Zenna said; then in a fond gesture pushed the other woman’s hair back from her face. She stopped short, and made a sad sound.

The other woman made a wry face. “Yes it’s very bad, isn’t it?”

“I’m afraid so. Oh, Berry, I’m sorry…”

“Never mind. At least I’m spared the sight of my own reflection.”  Berry’s face was in fact very beautiful, with a delicate nose, clean brows, a fresh complexion. Her mouth was wide, perhaps too wide; but it often happens with true beauty that a single unusual feature improves the whole. It draws the gaze, makes one notice, makes one think, and spares its owner the blandness of perfection.

Unfortunately, in the midst of all this were Berry’s eyes.

They were dark brown, but in the left eye the color of the iris seemed to have bled wildly into the white on one side. The pupil seemed to have forgotten its proper shape, and was oblong instead of round, a very disturbing sight. Berry’s right pupil was a tiny, frozen black spot, difficult to find in the murky brown iris.

Zenna’s face was a wince of sympathy. “Can you see at all anymore?”

Berry studied her. “You’re wearing a blue skirt and a very bright yellow blouse. And either you’re wearing your hair longer these days, or you’ve got a black kerchief on.”

“One advantage of not being a traveling steerswoman any longer — it’s so much easier to keep long hair. You’re still wearing yours short.”

“Josef likes it.”

“Where is he?”

“Somewhere about. But whatever he’s up to, I’m certain it involves animals.”

Zenna arranged her crutches on the floor beneath the table, settled herself more solidly, then looked about. “How does one get tea in this place?â€

“One generally goes to the kitchen door and complains; although they’ve taken to keeping an eye out for my needs…Â Let’s see if waving works.”

“No good. I don’t see a server to wave to.”

Two tables over, one of the other steerswomen noticed, and stood. “I’ll fetch, Berry,” she volunteered. She was a small woman in her fifties, dark-skinned, blue-eyed, gray-haired. “What do you need?”

“Keridwen, thank you.  Tea for Zenna and me, if you please.” Keridwen bustled off. “I’m glad you came,” Berry continued to Zenna. “You’ll tell me all about Alemeth, won’t you? Don’t leave anything out.”

“Of course.. and I’m glad to see you, too,” and Zenna shifted uncomfortably, an action lost on Berry. “Although…”

“You’re surprised I’m here?”

“…Yes…”

“So am I.  I was very surprised when the Prime’s message turned out to include me. But I’m glad. The journey alone was worth it.  A new environment — smell those flowers! And the mist by the falls, and there’s so much light here!  The station where we were living is tucked in a forest; walking around there, I might as well have kept my eyes closed. Still, I do wonder how much use I’ll be…”

“Don’t be silly. You’re an intelligent, educated woman, who has more patience than all the steerswomen in this room combined. And we’re going to need patience.”

A smile. “Thank you. But this little voice in my head keeps saying, ‘You don’t belong here.'”

Someone said: “The little voice is absolutely right.” The man had approached from behind Zenna. She turned, with an angry expression ready on her face, which vanished when she recognized him, and then became simple astonishment.

“Berry shouldn’t be here,” the man said. “And I definitely shouldn’t be here.” He carried a cozy-covered teapot and not two cups, but three. He set the china on the table, added a small plate of honey-buns.  “Neither of us should be here, but here we are.” He sat. “I don’t know what the Prime was thinking. We have important things to do, and dangerous ones at that. Did I complain when she sent me off into unknown lands, sneaking about and like no proper Steerswoman should, searching for a secret wizard’s keep? Not I. Best person for the job, apparently, so I dug in and did it. But then, all of a sudden, it’s ‘Drop everything and go to Logan Falls.'” He paused, considered Zenna’s expression disparagingly. “Don’t gape, girl. It’s rude.”

Zenna closed her mouth, which had been hanging. She said, in a voice of disbelief: “Arian?“

“Of course.  Whom did you expect? King Malcolm? The man from the Moon?”  He picked up a honey-bun and bit it.

Zenna recovered, and studied him. “Hard work seems to suit you,” she commented.

“Hmph. I’ve worked hard my entire career. I merely hadn’t been using my body to do it, for the last decade ore so.”

Arian was of average height, of middle age. His forehead was high with a receeding hairline. His crisp hair had been black once, but was well on the way to salt-and-pepper. His beard, which he wore close-trimmed, was completely white. Arian was lean, and strong, and his skin was sun-dark, weather-rough, but healthy.

“Your color has faded in one direction and darkened in another. And how is it that you manage to look both older and younger at the same time?”

“The ‘older’ is my vast accumulation of knowledge and wisdom, a never-ending process. My sagacity increases year by year; I astonish even myself! The ‘younger’ is exercise and mental challenge.”

The door opened with a bang, followed by a small commotion, some apologies for the unintended noise, and the clearly-heard and somewhat plaintive question: “Isn’t anyone going to do anything about all those girls outside?”

“Ah,” Arian said, helping himself to another honey-bun. “And, did I mention, Berry? Ingrud is already in town.”

“Zenna!” The woman who had entered now made her way across the room, moving like a small hurricane, causing persons in the path to quickly shift their chairs. “Oh, look at you, I’m so happy!”  Arrived, she held out her arms, waiting for Zenna to rise and embrace her, then seemed to remember something, and her faced fell. “Oh!” She leaned down instead, wrapped her arms around the other. “Oh, I heard, I’m so sorry –“

“No, it’s all right –“

“But, but, your leg!”

Zenna extracted herself, held Ingrud’s hands, and spoke to her definitely. “I love living in Alemeth. There’s so much good work to do at the Annex, and the people are wonderful. I feel quite settled and happy.”

“But –“

“And I’m used to one leg by now. It’s been nearly five years.”

“Oh…” Ingrud said again, and cast about, found a chair, pulled it in, and sat. “If you say so…” But she embraced her friend again, then suddenly pulled back and rose and reached past her. “And Berry! I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to neglect you.” Another hug, a bit awkward, as Ingrud left one hand on Zenna’s shoulder, as if reluctant to let her go.

“It’s all right. We’re all going to be here for a long time. There’ll be plenty of opportunity to catch up.”

“Catch up,” Ingrud said, pushing her cloud of wild hair back from her face. “I’ve been catching up since I got here. Incredible stuff; I’ve been completely out of contact since –” and she turned back to Zenna — “since the last time I saw you. And since then —  all that’s happened!”

Arian said: “You may have had no contact with us, but we had plenty with you.” Ingrud turned to him. “Your logbooks arrived at the Archives regularly, while I was there,” he continued. “I don’t think we lost a one in transit.” He paused; Ingrid said nothing. “Very good work, by the way.” Still nothing. “Oh, go ahead, get it over with.”

“Arian?“

“Excellent. Good reasoning on your part, Ingrud –“

“Whatever has happened to your paunch?”

“My longtime companion, yes.” He slapped his stomach. “It decided it no longer liked the environment, and vacated the premises.”

Ingrud blinked. “Well. You look wonderful.” Her tilted green eyes grew speculative. “In fact, if you were twenty years younger –“

“Please. Ten would do it, I think.”

“Well, I’ve always been attracted to older men. They’re not idiots. Usually.”  She recovered her chair. “And look at this, here we are. I didn’t think any from our class would be asked to come, I was so surprised! Who else of our group is coming?”

“I have no idea,” Berry said.

“Well, who’s missing?”

Zenna said: “Janus.”

The table became silent. Then Ingrud nodded at some internal thought, sighed, shook her head as if at another thought, seeming half-disbelieving; then nodded again, sadly.

“Make up your mind,” Arian said.

“I did, back when I saw him. Before he settled in Alemeth, I’m assuming, that was. He was just… so wrong. Aside from refusing to answer my questions.  Everything about him was off, strange, and just wrong.  Even the music he played.”

All were silent for a few moments, lost in separate thoughts. Then, with visible effort, Berry roused herself and changed the subject.  “Speaking of music, has Mona survived the road?”

Ingrud brightened. “Well… I had to glue some cloth tape over her low D, the valve was stuck open. Other than that, she’s in fine voice. I hope I can find someone to repair her.  We’re learning sea-chanteys. There seem to be a lot of new ones.”

“Isn’t that rather a contradiction?  Aren’t all sea-chanteys old?”

Several spoke at once.  “That couldn’t be so.”

“Not at all.”

“Even the oldest must have been new at some point.”

“There’s one about a mermaid who loved a dolphin,” Ingrud said, “and convinced him to marry her. But, and here’s the interesting part, the dolphin agreed only if she would also marry all of his brothers, too. And that’s what they did. There’s a verse for each brother on the wedding night.”

“Well,” Zenna said, “as long as she actually agreed. And did they have children?”

“The song doesn’t go that far. But I suspect that the offspring will show up in songs or tales sooner or later. It’s too lovely a concept, just dripping with poetry and tragedy!”

“All necessary components for a good song,” Berry said.

“Do you know what I’m finding interesting?” Zenna said, looking around. She subtly indicated the room in general. The others caught her gesture. They did not ask, but as one, adopted a remarkable manner, where it was obvious that they were taking in the entire room and its contents, without glancing about wildly, but seeming to open up and let everything in, and evaluate and analyze what they saw.

The exception was Berry, who first reacted only to the fact that the table had gone silent, and then adopted a version of the same pose, but with head slightly tilted, listening. She smiled. “And to what are we attending?”

“The fact,” Arian said quietly, “that we are being closely watched.”

“I wonder what they want?” Ingrud said, as softly.

“Who?” Berry asked; then answered herself: “The other steerswomen.”

“It’s really very odd,” Zenna said. “They’re so obviously ignoring us that it’s obvious that we’re the center of their attention.”

The door opened, and a steerswoman entered.

A flick of pause around the table, and then:

“Ah.”

“Hm.”

“Oho.”

“What?” This from Berry. The newcomer took three more steps. “Oh, that’s Edith.”

The steerswoman arrived at the table. “Ladies.” She nodded around. “Arian.” He acknowledged her greeting. She pulled a chair from a table nearby and sat. “Apparently, I’m supposed to sit here. Do we know why?”

Ingrud threw up her hands. “This is ridiculous.  They’re all steerswomen. If we ask them, they have to answer!”

“They’re treating us,” Arian said, thoughtfully, “almost as if we’re students.”

A pause. “So,” Ingrud said, “if we did ask them, they might say something like, ‘We could answer, but this is something we’d like you to reason out for yourself? And, do you still want us to answer?'”

“It’s rather insulting, actually,” Edith said, then slouched more comfortably in her chair, extending long legs to one side. She was a remarkably tall woman, sun-bleached and sun-browned. She sounded not at all insulted.

Ingrud made show of gritting her teeth in exasperation. “I hate suspense.”

Edith shrugged. She glanced once at Arian, sidelong, glanced away again.

He said, “Aren’t you going to remark on how changed I am? It seems quite the topic today.”

“You look exactly as you did when you were my teacher, but twenty-five years older. Apparently, your appearance since then and before now was just a passing phase of indolence. You look like yourself.”

“Hm. You were always a practical girl.”

The door opened. “None of the girls out there know what they’re doing,” the woman who entered announced to the room at large. “And I think they’re afraid to enter. They know that all the steerswomen are in here. If it rains, I do believe they’ll just stand there and get wet.”

“Excellent,” Arian replied. “Then we can eliminate them all as being too simpleminded to qualify. With luck, no one will qualify at all, and we can give up the enterprise entirely and all go back to our regular tasks.”

“We need them,” the woman said, and with no hesitation crossed the room to join the five. Arrived at the table, she paused. She was full-bodied, bright-eyed, iron-gray, somewhat older than Arian. “They’re the next generation, or some of them are.”

“With Shayna here, we need a bigger table,” Ingrud said, and looked around for a better one.

“Or, there are too many sitting at this one,” Shayna said, off-hand.

Edith looked up at her sidelong. “Oho.”

Shayna raised her brows. “Yes, what?”

“She knows a thing or two,” Edith said. Then she rose and offered her chair to the older woman. Shayna sat. “Tell me lady,” Edith said, “who should not be sitting at this table?”

The others stopped short, looked at Edith, then turned their regard on Shayna.  She returned their gaze. “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to be rude. There’s no reason anyone shouldn’t sit anywhere they choose.”

Edith said, from above Shayna’s head: “It was suggested that I sit with Ingrud and Arian. NOthing was said to you?”

“No. No one made any suggestions.”

Ingrud said, “Why don’t we just ask?”

“Ask what?” Shayna said.

“Why everyone is watching us so closely, while trying to look as if they’re not doing it at all,” Ingrud said with feeling. “A steerswoman can’t lie, but we’re free to dissemble. Except, we’re very bad at it. Well, most of us are. Everyone is carefully not saying something important.”

“And meanwhile,” Berry said, setting aside her knitting, “does anyone have any idea when matters are going to begin? At the very least, let’s invite all those girls in if it really is going to rain. And it certainly feels as if it’s going to.”

“We can’t just sit about uselessly until the Prime arrives,” Zenna said.

“And does anyone know when that will be?” This from Ingrud. “Is she still too ill to travel?”

Edith said, “She seemed to be stronger when I saw her two weeks ago.”

In the middle of this, Arian suddenly sat straighter. “That’s it.”

Ingrud threw up her hands. “What? Really, someone does have to speak!”

Arian looked at Shayna, but it was to the other women that he spoke. “The rest of you didn’t see it — it was before your time. But I was a student then, and Shayna here one of my teachers.” He turned to the others. “Usually, it’s the Prime who decides when things start at the Academy, and she’s in charge. But when I was a student, it didn’t happen that way. Because the Prime was absent. And not because she was ill.”

Ingrud stood up. “I’ve had it!” She addressed the room at large. “Someone please tell me what is going on.”

Across the room, a slim woman with wildly-curling gray hair and a very kind smile spoke up immediately. “You’ll need to be more specific. Your question is far too broad to answer.” A few other women present laughed a bit; others laughed also, apparently at the laughter of the first ones.

Edith raised her voice to be heard by all. “Tell me, lady,” she said, using the formal phrase, “– and I’ll take the answer from any steerswoman in the room… by what process does someone become Prime of the Steerswomen?”

Ingrud, still standing, said, “What?”

On the far side if the room, one of the other steerswomen spoke up. “Generally, the person who is currently serving as Prime has a number of candidates in mind.”

Another steerswoman, Keridwen, spoke while continuing to pour tea for her table-mates. “But she takes it no further than that.”

“But,” and Ingrud looked about the room, at the other steerswomen, and at those sitting at her own table, “but, how does it finally come down to just one?”

Arian said, thoughtfully, “The next Prime is given the opportunity to, let’s say…. rise out of chaos.”

Edith said: “And this looks like chaos to me.  A crowd of girls out in the yard, not knowing what to do or where to go; a flock of steerswomen enjoying their tea inside; no visible plan, no apparent organization –“

Ingrud sat down, puzzled. “We have to invent the Academy? Ourselves? Right now? No, hold –” And she became visibly stunned. “Me? I’m one? And — and, us?” She looked at the faces around the table.

Berry had her head tilted down, her brows knit in thought.

Edith, still standing behind Shayna, nodded fractionally, chewing her lip.

Shayna drew a long breath, released it, folded her hands before her, and one by one, regarded the others calmly, waiting.

Arian sat very still, his eyes focused on some far internal distance, breathing quietly, as if tracking some prey he might startle.

Shayna said: “We need to sort those girls out. We should gather them, and send off any spectators. Someone should address them, and identify the ones who have already acquired accomodations –“

Arian said, without altering his expression in the least: “Shayna, do shut up.”

She drew herself up. “I beg your pardon?” she said stiffly.

He broke from his internal study, and turned to her, now very present and keenly focused. “Obviously you already knew about this, and you’ve given it some thought. You’re prepared.  But this is news to the rest of us, so please be considerate enough to allow us a few moments to assimilate the information.”

“But something does need to be done, and soon. While we’re sorting ourselves out, a crowd of girls are all at loose ends, and possibly frightened, far from home –“

Berry set down her knitting and stood.  She addressed the room at large. “Have all the adjunct teachers been contacted?”

A dark-haired woman seated by the window spoke up. “Yes.”

“Helena, thank you,” Berry said, turning toward the voice. “And have they all arrived?”

“No.”

“Which are present, please, and which are missing?”

“We have a herbalist, a beastmaster, and a hunter on hand. We’re drawing on the locals for a carpenter, bricklayer, blacksmith, seamstress, cobbler, leathermaker, and cook, so of course they’re already here. Still on their way are the healer, bookbinder, and swordmaster.”

“Thank you,” Berry said, and sat. She spread her hands, and spoke to those at her table. “That was by way of a test. Although apparently we are in charge, we can’t possibly be expected to personally do every task that needs doing. Some things are already in place, some organizational neccesities already addressed. We should discover what those are.”

“And meanwhile, the students are milling about at loose ends in the yard,” Edith commented.

“As I said,” Shayna said.

“I’ll need a chair,” Edith said absently, and looked about. All other chairs were occupied.

Zenna rose, her chair scraping loudly. “Take mine.” She fumbled, gathering her crutches from beneath the table, suddenly clumsy.

“Zenna, don’t be silly, sit down –“

“I shouldn’t be here.”

“I’m sure that the Prime had good reason –“

“No!“ The others stopped short, turned to her. “You were told to come to this table — but I wasn’t. I’m not — I’m not one of you, I’m not a candidate at all.”

Ingrud put a hand on her arm. “Zenna –“

Zenna shook it off. “And, and, I shouldn’t be here at all — not here in Logan Falls, not at the Academy. Or what will become the Academy. All of you — ” and here she raised her voice a bit, speaking to the room. “You were all asked to come here. Not every steerswoman is here — some of us are still out in the world, at our work. But every steerswoman who is here now: by words or letter or message, you were asked to come to work at the Academy. Am I right?” Nods all around. Zenna looked down. “But I wasn’t.  I was not ordered, asked, or invited. Nothing was said to me about coming to the Academy.” She made a helpless gesture. “I just came. Because I wanted to.” She fumbled with her crutches, managed to position them. “So, I’ll leave you to this.”

The others glanced at each other, disturbed but resigned to it.

Except for Berry. “Zenna, please stay.”

“I’ll stay for a while,” and she began moving, “but with them.” At a nearby table, another steerswoman rose to offer her seat.

“No, Zenna. Stay here, with us,” Berry said. “Please.”

The young woman stood stopped in the middle of the room, said bitterly:Â “Why?“

“Because I need eyes.”

Zenna turned, looked back.

The others were staring at Berry.  Arian said, hesitantly, “But, Josef…”

“My husband reads books for me, and tells me where my teacup is, and stops me stepping into dog droppings. And describes how beautiful the sunset looks. But for this, I think I need a steerswoman’s eyes. And I don’t have them.”  She reached out one hand. “Zenna?”

Ingrud leaned back in her chair, said quietly: “Oh, perfect, perfect.”

Shayna’s face lit up, spontaneously, brilliantly. “That’s lovely.”

“Hm,” Arian said. “Well, there you go.”

Edith watched, waiting, head slightly tilted.

Zenna, at last, drew a breath and came back. “Thank you.” She took Berry’s hand, and sat, then arranged herself again, and looked about. “And now Edith doesn’t have a chair again.” She laughed a bit.

In fact, Edith looked, for the first time, uncertain. She hesitated.

Arian said, “Skies above, girl, just tell someone to give you their chair.”

“Go ahead,” Ingrud urged her. “We’re in charge. Apparently.”

Berry said to Zenna: “Tell me the look on her face.”

“She really doesn’t want to. But she thinks she ought to.”

“She doesn’t want to give people orders, I think,” Berry said.

Ingrud threw up her hands. “She gave us orders constantly! When she was our teacher. At the last Academy.”

“You were her students,” Arian noted. “But these steerswomen were her teachers when she was a student herself, some of them.”

“I’m actually present,” Edith commented to the table. “I’m actually able to hear you, you know.” She made a noise of frustration. “And I’m certain that there are more chairs available somewhere in this house.” She strode off, toward the serving entrance.

Shayna called to her: “Bring two chairs.”

Arian smiled. “You sly creature. There’s another, isn’t there?  Who else is coming?”

The door opened, and a steerswoman came in.

Well. There you go.

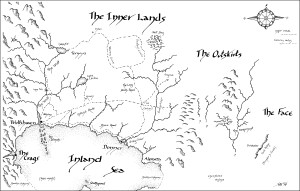

For reference, here’s a map. You may click to embiggen.

Back to those other tasks, some of which I may discuss in detail fairly soon…